Plenary adoption is what is generally meant when we talk about adoption. It is the legal mechanism by which a child is placed permanently into a family and becomes the child of a new parent or parents. In the UK, the original birth information is placed on the Adoption Register, a sealed record which the adoptee can only access once they turn 18.

What happens to birth certificates?

An Adoption Certificate is issued which the adoptee will use instead of a birth certificate. This includes the date and place of birth, and the adoptive parent or parents’ names. The original birth certificate can be requested by the adoptee, from the age of 18.

Most children who have been adopted are aware but there is no legal requirement for an adopter to tell a child they have been adopted. This has led to many adoptees discovering later in life (Late Discovery Adoptees/LDAs) and some may never know at all, if they do not order a birth certificate.

What about health information and records?

A health report is prepared before adoption takes place so some information is available to adopters but once adoption has happened the NHS is required to close that child’s health record and open a new one, not linked to the old one, in order to maintain the secrecy about their original identity. This means that adoptees do not have a family medical history and that information about health conditions that show up in the birth family after they have been adopted out is not passed on. They also are unaware if a birth relative has died and what caused their death.

Is there any other kind of adoption?

Arguably step-parent adoption does not completely erase a child’s identity, though the parentage is still changed legally. It is less common these days as there is reduced stigma about having different names within families and about non-traditional families.

You may also hear about ‘simple’ adoption in some countries. This is an adoption in which the legal relationship between the adoptee and the birth family is not severed.

What about open and closed adoptions?

An open adoption is an adoption in which the child’s birth identity is not hidden and some kind of relationship with birth family is maintained. It is important to be aware that there is no such thing as an open adoption in UK law. If there is contact with birth family it is often indirect, sanctioned and mediated by social workers and adopters, and can be withdrawn at any time.

What’s wrong with adoption?

Here are just a few things:

1. It commodifies children. In other words, it is legalised trafficking and in the future we believe it will be viewed this way by society. A child is not something to be acquired.

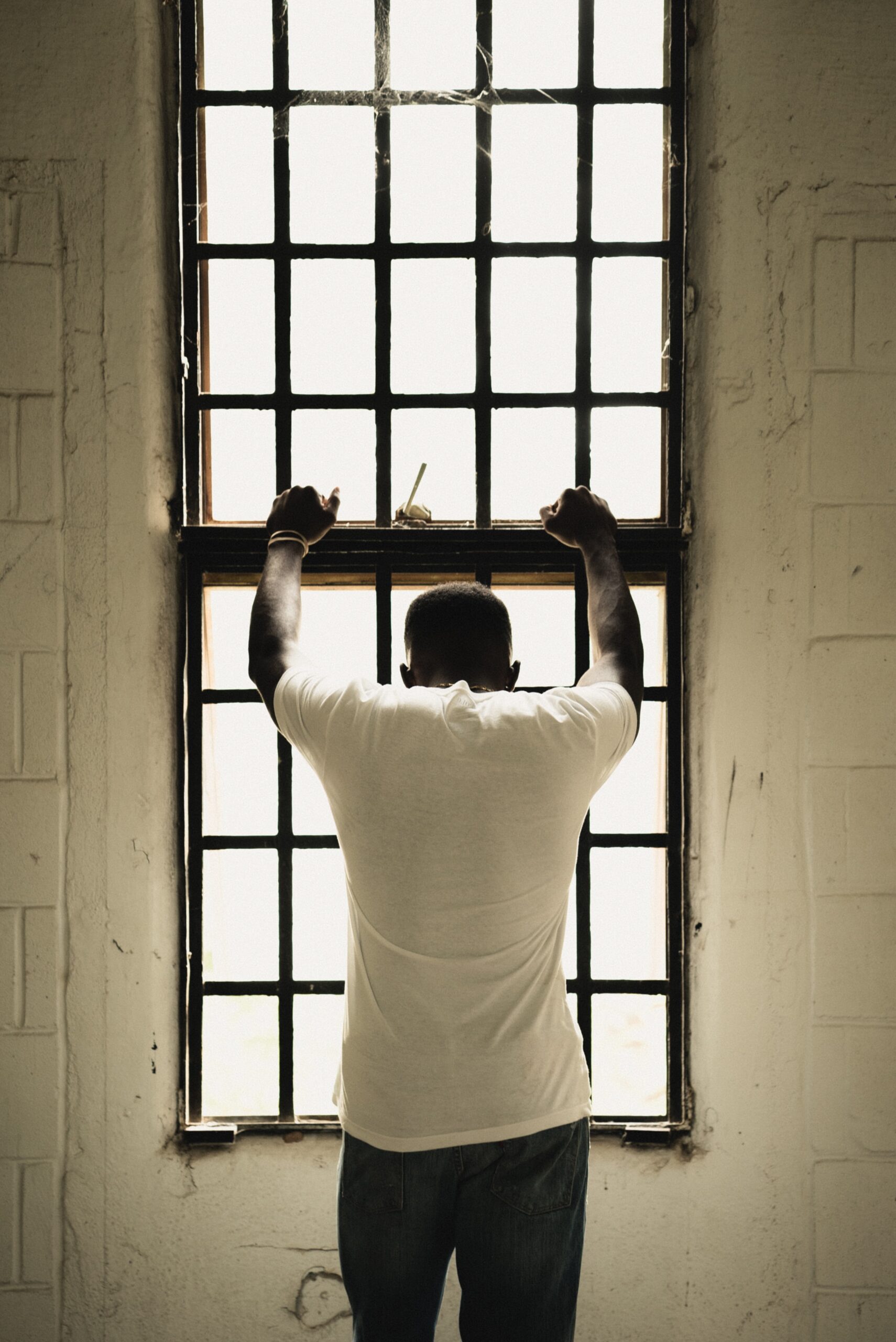

2. It erases identity and separates people from family and culture. This is particularly egregious in the case of transracial and inter-country adoptions.

3. It creates a set of relationships with power imbalances built in. Children are groomed to be ‘grateful’ they have been adopted when in reality, it may be a source of great sadness to them. They are not necessarily told the truth about their families of origin. Contact with birth families can be vetoed by the adopters.

4. It romanticises family-building, encourages saviourism and attracts narcissistic parents who then view themselves as victims when the children act out. Don’t believe us? Check out the #adopteevoices hashtag on Twitter and see how many examples you find of narcissistic and abusive adopters.

5. It is irreversible. An adoptee is entered into a legal relationship with their adoptive family, removed from a legal relationship with their family of origin, and not given the option to release themselves from this contract or revoke the adoption. What other legal arrangement can you be entered into without giving consent, to which you are bound for life?

Don’t all children deserve a stable, loving family?

Yes—and this can be achieved in other ways without erasing their identities and severing them from all birth relatives. Kinship care, special guardianship and long-term foster care are some options. Children are not something to be ‘owned’. And sometimes more could be done to support children staying with their birth families rather than being taken into care in the first place.

And what about those who are unable to give birth? What about LGBTQ+ families? What about single parent families? Doesn’t everyone have a right to be a parent?

Well, no. Parenting is a privilege, not a right. And adoption is by no means the only path to parenting. And even if it were a right, surely the rights of a child trump the rights of an adult?

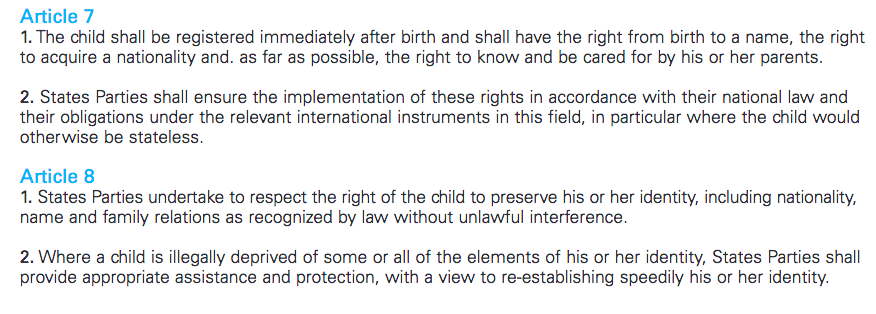

What do you mean, the rights of a child?

Everyone has the right to security, food, shelter, and to have their basic needs met. Beyond this, there are rights to family life and rights about identity. There is a UN Convention on the Rights of the Child to which the UK is a signatory, though you wouldn’t necessarily know it from looking at our outdated adoption laws.

What if birth family pose a threat to the child?

If, for safeguarding reasons, it is necessary to change a child’s identity then that should not be irreversible—the threat may later go away. Plenary adoption makes it irreversible. Permanently changing a child’s identity allows adopters and social workers to demonise a child’s birth family and blame any problems the child is having on the abuse or neglect they suffered before they were adopted. This is not the whole picture—it ignores the traumas of separation and of being placed with, and dependent on, strangers who are not biologically related to you. As baby-scoop era adoptees we are the proof—we were not abused before adoption and usually not neglected but we still carry these traumas. These imprint on the brain and affect development but it’s easier to blame the birth mother’s behaviour so some diagnoses have become fashionable.

(In general, diagnosis can be useful because it identifies a cluster of symptoms and suggests some possible interventions but it’s more important to identify the underlying cause, which in the case of adoptees is often trauma).

The early separation can also cause us to feel worthless and unwanted, so we are susceptible to further abuse.

What about child protection?

As long as plenary adoption is an option, those responsible for child protection will be inclined to think of it as an easy—and cheap—solution when there are child protection concerns. Adoption means the local authority is no longer directly responsible for that child’s care. Money to support adoptive families comes from the Adoption Support Fund. Voluntary Adoption Agencies charge for placing a child (currently over £38,000) and that is still a bargain to local authorities in the long term. And child protection is not always about abuse; sometimes it’s about poverty and resources.

What can we do to support alternatives?

Charities such as Kinship and Family Rights Group are working to help families stay together and to support kinship carers where possible. The government’s response to the Care Review is somewhat encouraging in this regard. And please: adopt a pet, don’t adopt a child.